It’s over eight years since I’ve posted anything on this site and it took Shane MacGowan to get the words flowing. I’ve just watched a brilliant film festival documentary, ‘Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan 2020’, in which the former Pogues frontman and songwriter opens up about his life and Ireland’s tumultuous history.

‘Opens up’ probably overstates it because after a lifetime thrashing himself with drugs and alcohol, MacGowan is bloated and barely audible. His words are sub-titled. But the spark still glows inside the man Clash leader Joe Strummer described as ‘Ireland’s greatest songwriter of the 20th century’.

Under the influence of punk, MacGowan sought to ‘kick Irish music up the arse’, as he put it, and drag it into the twentieth century. But Crock of Gold’s most striking section is MacGowan talking about childhood holidays running wild at his extended family’s Tipperary farm, not far from where my Martin forebears come from. I wrote about this in an earlier blog after reading his biography but the doco with its animated graphics, old video and film clips, photos and music brings it alive.

At age five, his Aunty Nora showed him how to place a bet and introduced him to cigarettes, Guinness and stout. All of which were fine so long as he went to Mass. From his big clan MacGowan gained a love of music and a mystical sense of his Irish heritage. He loved the old people, the ritual of the Mass and tales of faeries and Irish folk heroes. Family stories included his great-grandparents in the Land League in the late 1800s and sheltering IRA men from the Black and Tans in the 1920s.

In the Pogues’ song, ‘Broad Majestic Shannon’, MacGowan writes about Glenaviegh and Finnoe and hearing ‘the men coming home from the fair at Shinrone, their hearts in Tipperary wherever they go’. It could be an anthem for the Martin diaspora. These places are down the road from the village of Terryglass where our Irish great-great grandparents, Michael and Mary Martin (nee Boland), once lived. Had they never left, I may have shared an upbringing as poor and riotous as MacGowan’s.

At the time Michael and Mary sailed for New Zealand, Catholics—that is, most of the Irish—were forbidden to own the land they had inhabited for centuries. English settlers had begun clearing Tipperary’s woods, filling the bogs and building farms after Cromwell’s conquest. Catholics had to rent. Michael was a tenant on George Cornwall’s farm. Mary’s father, Gabriel Boland, was a tenant on the Saurin brothers’ four-acre farm.

Ireland’s population had exploded to over eight million in 1853 from 2.5 million a century before. Landholdings were tiny and tenancies short with Tipperary known for the ruinous system of conacre, the renting of farmland for just one season or less than a year. Farmers who resisted and tried to consolidate scraps of land into viable plots were tossed out of their homes.

Landless labourers and small tenant farmers banded in secret societies to fight evictions, tithe gathering and excessive rents: the Whiteboys, Rockites, Oakboys, Houghers, Rightboys, Defenders, Threshers, Caravat Whiteboys, Ribbonmen. The Rockites were named after ‘Captain Rock’ and his skill at hurling rocks at bailiffs; the Whiteboys wore ghostly white smocks on night time raids to attack homes and beat or kill the occupiers. Catholic farmers were sometimes targets, usually for taking land from an occupying tenant at the end of a lease.

In 1822, a farmer named Boland in Terryglass, most likely a relation, had his cattle driven out under an eviction decree: ‘The constables were attacked by the peasantry, the cattle rescued, and one of the men named Larkin was killed!’ reported the London Times. In 1844, 254 cases of rural violence were reported across Tipperary. Michael and Mary lived amid this chaos for 50 years, through the Famine and beyond.

Their eldest son, Anthony, was the first to go, making his way to Yorkshire and working as a farm labourer. In March 1863, aged 21, he boarded the Metropolis in London, along with his sister, Ellen, 19, and his aunty, also Ellen, 31. They arrived in Lyttelton on 16 June 1863, the first of the Martin clan to step ashore in New Zealand.

From the passenger list of the Metropolis, 1863.

They saved, sent money home and wrote urging the rest of the family to join them. A year later, Michael and Mary and their five other children, John, Julia, James—my great-grandfather, then 10-years-old—Michael junior and Mary, arrived in Lyttelton and walked the steep Bridle Path over the Port Hills to their new home in Christchurch.

On the ancestral trail in 2004, I easily found Michael and Mary’s plot at Linwood Cemetery from cemetery records. But there was no marker, just a patch of dry grass and weeds. I later heard that a headstone had been placed on the site and, sure enough, when I visited again early in 2021, a simple plaque sat on a fresh concrete base among crumbling old gravesites. I don’t know who put the plaque there but, on behalf of Martin descendants around the country, thanks.

Michael and Mary gave the clan a flying start—when Mary died in 1890, she had 23 grandchildren. One was my grandfather, Bill Martin. He helped pass on the name of the trailblazer, Anthony[1]. Dad was John Anthony, Bill having named him in classic Irish fashion after two of his own father’s brothers, including the eldest. ‘Anthony’ was handed on to me and is also my middle name.

According to a Press obituary on 3 May 1890, Mary was ‘an old identity of a kind and amiable disposition’. She lived in Caledonian Road on the corner of Keoghs Lane in St Albans for over 26 years. The Caledonian Hotel was two minutes’ walk away and Michael nicknamed their home ‘The Cal’. After the cemetery visit I decided to look at the old street. Apart from a few renovated cottages, houses from that era are gone. Post-quake apartments and townhouses, all grey and black boxes, are crammed everywhere. New builds sit on the corner of Keoghs Lane and townhouses occupy the site of the old pub which was pulled down in 2010.

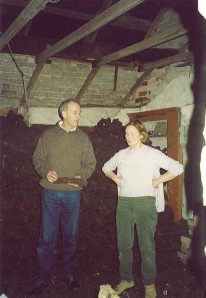

The Martin name lives in Canterbury electoral rolls, records and newspaper snippets but except for the new cemetery plaque, no physical markers of the family remain. It’s the same in northern Tipperary where the landscape reveals little trace of the Martins ever living there. Twelve years ago in fields around Terryglass I peered into old abandoned cottages wondering if the Martins or Bolands lived in this one or that. There’s a paddock known as ‘Jimmy Martin’s field’ but otherwise, of the Martins and thousands of other families who fled after the Famine, only old Irish records tell the story.

Except for mystics and poets like Shane MacGowan. They tell stories too. Something in that doco made me think again of the Martin family, their Irish origins and what they’d lived through, and their new memorial in Linwood Cemetery. MacGowan’s gift as a story teller is to rekindle deep memories that get passed on, and on.

[1] Anthony also put in a sterling effort to build clan numbers. He moved to Wellington, married 16-year-old Margaret (Harrington) and produced 18 children. He was a bootmaker and his shop, Martins shoe store, operated in Courtenay Place then Mercer Street for many years.

Posted by Pat Martin

Posted by Pat Martin